Friendly International

Olympiastadion, Berlin, 14.05.1938

![]()

3-6 (2-4)

Gellesch 20., Gauchel 44., Pesser 77. / Bastin 16., Robinson 26., 49, Broome 28., Matthews 42., Goulden 80.

Germany: Jakob – Janes, Münzenberg – Kupfer, Goldbrunner, Kitzinger – Lehner, Gellesch, Gauchel, Szepan (c), Pesser

England: Woodley – Sproston, Hapgood (c) – Willingham, Young, Welsh – Matthews, Robinson, Broome, Goulden, Bastin

Colours: Germany – red shirts, white shorts, black socks; England – white shirts, blue shorts, white socks

Referee: John Julien Langenus (Belgium)

Assistants: S. Mackenzie (England), Alfred Birlem (Germany)

Attendance: 105,000

Match Programme Details

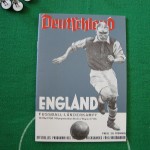

Priced at twenty Reichspfennig and containing a hefty forty printed pages, the official match programme for the 1938 fixture at Berlin’s Olympiastadion has an artistic image of a player on the cover in the style of the times. The distinctly Nazi take on the German language also affected football programmes – rather than “Fussball-Länderspiel” – as had been the case before and since – the term “Fussball-Länderkampf” was used instead. It was a “struggle” rather than a “game”.

After the welcome statement from Reichssportführer Hans von Tschammer und Osten, the programme contains a detailed history of the fixture as well as excellent illustrated pen-portraits of the players from both sides.

My own copy of the 1938 match programme is a special limited-issue postwar reprint; originals are extremely hard to come by and – when they do become available – prohibitively expensive.

Aspect: Portrait

Dimensions: 210 x 148 mm (A5)

Numbered Pages: 40

Language(s): German

Match Report

If the game at White Hart Lane in 1935 had been clouded in controversy, then the encounter in May 1938 saw the clouds burst open in what has been seen by both football writers and historians as one of the most unsavoury tales to mark the beautiful game. As had been the case three years previously, it was not the players motivating the negative undercurrent but administrators and politicians – those who could best be described as interfering busybodies concerned more with scoring political points than letting the players do their thing on the pitch.

After their defeat at White Hart Lane in 1935, the German team had experienced a number of highs and lows. While the 1936 Olympic tournament provided home fans with a disappointing quarter-final exit at the hands of unfancied Norway and the dismissal of Nationaltrainer Dr. Otto Nerz, 1937 had seen something of a renaissance under new coach Sepp Herberger and the development of what became known as the Breslauer Elf – the first legendary German side.

During the course of 1937, Herberger’s side had played a total of eleven games with ten wins and a draw and had come into the game against England on the back of an unbeaten sixteen-game run; these impressive-looking statistics however provided a deceptive disguise for a team that was about to embark on a tumultuous period where they were to be turned first into political pawns – and then into an embarrassment.

On 12 March 1938 German forces marched into neighbouring Austria in what was a bloodless invasion and occupation; within a month, the country had ceased to exist having been incorporated into a greater German Reich. The annexation of Austria not only saw the disappearance of the country itself, but also its legendary football team – whose members now found themselves available for the German national side.

Keen to exploit the situation, government agencies almost immediately applied pressure on Herberger to select these newly available players; while on paper the addition of the highly-skilled Austrians looked set to create an unbeatable team, in reality it saw the gradual dissolution of the Breslauer Elf and their replacement with players whose hearts would never really beat for Germany. Not only was Herberger forced to build a single squad from two teams that in truth didn’t like each other very much, he also had to produce a “balanced” pan-German side – one consisting of six of one and five of the other. It was the sort of abject nonsense that provided every justification to the belief that sport and politics – of whatever hue – just do not mix.

To complicate matters yet further, the English FA had demanded that no Austrian players turn out for the Schwarz und Weiß in Berlin; in the event, one of them did play – SK Rapid Wien’s Hans Pesser.

While Sepp Herberger and the German side were having to put up with political meddling in team selection, the English FA were having problems of their own – with the biggest concern being how the players should stand for the playing of the national anthems. Were they to offer the Hitlergruß or simply stand to attention? Were the players to be allowed to make the decision for themselves, or was there to be a directive from above? In the end, all eleven players raised their right arms to the playing of the Deutschlandlied – drawing roars of approval of the home crowd and creating what soon became something of a scandal back in England.

It soon became fashionable for outsiders to condemn the team, and after the war – from all accounts I have read – it became equally fashionable for the players themselves to suggest that they were somehow coerced into it. The truth is probably somewhere in between: the position of the Government at the time was one of appeasement, and having the national football team offer the Nazi salute as a mark of respect to their hosts would hardly have been seen as extraordinary; as for the players themselves, it is probable that at the time they really didn’t care that much either way.

Given Germany’s record coming into the match, the result was highly disappointing for the home side as they went down by six goals to three on what was a blisteringly hot May afternoon. Although ten Germans and only one Austrian were on the field, the political interference had clearly had an effect on the team’s gameplay as they seemed to lack both spirit and coordination. The Mannschaft had levelled the scores through Rudi Gellesch after Cliff Bastin had given England the lead, but a sixteen-minute spell then saw the visitors storm into a 4-1 lead. Germany did manage to pull a goal back through TuS Neuendorf’s Jupp Gauchel just before the break, but normal service was resumed when Sheffield Wednesday’s Jackie Robinson scored his second of the match four minutes into the second half to make the score 5-2. West Ham’s Len Goulden restored England’s four-goal cushion on seventy-seven minutes, before the Austrian Pesser scored a late consolation three minutes later.

England had emerged victorious, and the German team failed to live up to the hype – even though the players themselves accepted that their opponents were by far the better side.

The use of the German national team as a political plaything carried on into the World Cup Finals the following month; here the plan of fielding an artifically-constructed pan-German team completely unravelled before the tournament had really begun. With the skill, grace and style of the great Breslauer Elf now a distant memory, a disjointed side fell at the first hurdle – the only occasion that any German side has failed to get past the first phase.

Cumulative Record

Home: played 5, won 0, drawn 2, lost 3. Goals for 9, goals against 19.

Away: played 2, won 0, drawn 0, lost 2. Goals for 0, goals against 12.

Overall: played 7, won 0, drawn 2, lost 5. Goals for 9, goals against 31.