FIFA World Cup Semi-Final

Stadio delle Alpi, Torino (ITA), 04.07.1990

![]()

4-3 PSO (0-0, 1-1, 1-1 aet)

Brehme 60. / Lineker 80.

Penalties: Lineker 0-1; Brehme 1-1; Beardsley 1-2; Matthäus 2-2; Platt 2-3; Riedle 3-3; Pearce SAVED; Thon 4-3; Waddle MISS.

Germany: Illgner – Augenthaler – Buchwald, Kohler – Berthold, Häßler (66. Reuter), Matthäus (c), Thon, Brehme – Völler (38. Riedle), Klinsmann

England: Shilton (c) – Walker, Wright, Butcher (70. Steven), Pearce – Parker, Waddle, Gascoigne, Platt – Beardsley, Lineker

Colours: Germany – green shirts, white shorts, green socks; England – white shirts, blue shorts, white socks

Referee: Jose Ramiz Wright (Brazil)

Assistants: Joël Quiniou (France), Armando Perez Hoyos (Colombia)

Yellow Cards: Brehme / Parker, Gascoigne

Red Cards: – / –

Attendance: 62,628

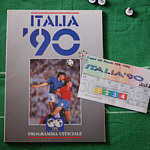

Match Programme Details

There were no individual match programmes published during Italia ’90, only the official 114-page tournament guide. The copy in my collection has no cover price, so I can only assume that this was either indicated elsewhere or that the programme was included in the cost of a match ticket. The image on the cover shows Italy’s Carlo Ancelotti – now manager of Chelsea – beating Spain’s Emilio Butragueño in the air during Euro ’88.

For most major tournaments different versions of the tournament programme would be printed in different languages; my copy is an original Italian version. The publication contains introductions by FIFA Presdent Dr. João Havelange and the head of the organizing committee Luca Cordero di Montezemolo and portraits of all twenty-four competing nations.

Aspect: Portrait

Dimensions: 285 x 210 mm

Numbered Pages: 114

Language(s): Italian

Match Report

The 1990 encounter in Turin between Germany and England was without doubt one of the classic encounters between the two teams. Over two hours of football played, the drama of a penalty shootout, and Gazza’s tears. For England fans, it was yet another so-near-yet-so-far story in a growing list of heroic failures; for supporters of the Nationalmannschaft, it was not only another semi-final victory, but one that was appreciated not just by sixty-million western Germans but also another twenty million in the soon to be defunct German Democratic Republic. The next meeting between the two sides at Wembley the following year would see Germany return as a reunited nation.

Both Germany and England had progressed to the semi-final unbeaten, but in contrasting fashion. Bobby Robson’s side had scraped through its first phase group with draws against the Republic of Ireland and the Netherlands and a narrow 1-0 win against Egypt; their second phase match had seen them grab a late winner in extra time against an unlucky Belgian side, and an exciting quarter-final had seen them come from behind courtesy of two Gary Lineker penalties against the surprise package of the tournament, Cameroon. Franz Beckenbauer’s Germany side on the other hand had stormed through the opening phase with ten goals in three games: a stunning 4-1 opening win over perennial tournament dark horses Yugoslavia had been followed by a 5-1 demolition of debutants UAE and a 1-1 draw against Colombia, while the second phase saw what was in German minds the most memorable game of the tournament where the Netherlands were beaten 2-1 in a ten against ten classic. The quarter-final was by contrast a more workmanlike and straightforward affair, with a first-half Lothar Matthäus penalty taking them through against a hard-working but somewhat toothless Czechoslovakia.

No sooner had the English media realised that there would be yet another World Cup finals encounter against “the old enemy”, the age-old propaganda offensive went into overdrive. It was hard to believe that more then forty-five years had passed since the end of the Second World War, yet British audiences found themselves being regaled with the same old nonsense. Even for those of us who had been brought up on a diet of jingoistic war films and comics like myself, the gutter press offensive went way beyond what could have been described as simple light-hearted banter; while jibes about mullets, female underarm hair and the Teutonic predilection for Freikörperkultur could have easily been laughed off, images of Hitler and the constant refrain of “two world wars, one world cup” – and various derivations thereof – were not in the slightest bit funny. It was clear that some people had way too much time on their hands.

Thankfully, the two teams themselves had decided to concentrate on playing football – delivering what turned out to be a highly sporting contest in what had generally been a tournament marred by unsportsmanlike behaviour and gamesmanship.

The German team that lined up at the Stadio delle Alpi was markedly different from the eleven that had inflicted the 3-1 defeat on England in Düsseldorf three years earlier, and was the result of what had been a continued policy of tinkering and tweaking by Nationaltrainer Franz Beckenbauer to achieve the right balance between more experienced heads and younger players. Goalkeeper Eike Immel had retired after Euro ’88 to be replaced by the young 1. FC Köln stopper Bodo Illgner, the young Kölner Thomas Häßler was in a powerful-looking midfield alongside skipper Lothar Matthäus, and partnering Rudi Völler up front was the Mannschaft’s new Torkanone, Jürgen Klinsmann.

Bobby Robson’s England side also had a balance of experience and youth. Alongside old hands Wright, Butcher, Lineker and Beardsley were a number of individuals who playing their first game against Germany, among them defender Des Walker and a midfield consisting of Paul Parker, David Platt and the great hope of English football, Newcastle United’s twenty-three year old Paul Gascoigne.

Since the European Championship finals two years earlier both sides had only been beaten once: Germany had suffered a 2-1 friendly reverse in February in Montpellier against a French side that had failed to reach the finals for the first time since 1974, while England had gone down by the same score at Wembley against Uruguay in what had been their farewell home fixture before the tournament began. In the words of BBC match commentator John Motson, something had to give.

England started off brightly stright from the kick-off, winning three corners in the first minute – the second of which was earned after Bodo Illgner had spectacularly turned a Paul Gascoigne shot around his left post. With Bobby Robson’s side making all of the early running, the Germans – wearing their change kit of green and white for the first time in the tournament – were finding it hard to get a foothold on the game – winning their first corner in only the twelfth minute. While England were looking sharp in midfield, Franz Beckenbauer’s side were looking uncharacteristically sluggish – with the usually ubiquitous Matthäus looking somewhat anonymous. The first thirty minutes had been uneventful for England ‘keeper Peter Shilton, with the highlight being a long-range effort from Klaus Augenthaler than had harmlessly ballooned over the crossbar.

With just over thirty-two minutes gone, Rudi Völler collapsed in a heap out by the left touchline under a challenge from Paul Parker; he immediately beckoned to the dug-out, and within seconds the unmistakable figure of the diminutive physio Adolf Katzenmeier was rushing over. With Germany temporarily down to ten men, Chris Waddle then launched a shot from just inside the halfway line – forcing Illgner into a spectacular save. It wouldn’t have mattered as the Brazilian referee had already blown for a free-kick, but Illgner would not have known this as he tipped the ball over via the crossbar.

Rudi Völler meanwhile was still being treated out on the sidelines; as is usually the case in modern football, it is nearly always the innocuous-looking challenges that cause the most damage – and so it proved here. Some six minutes after he had summoned the physio, the tousle-haired marksman was slowly helped off the field and replaced by Karl-Heinz Riedle.

Völler’s departure appeared to signal a distinct change in momentum, as the Mannschaft started to find a little more space in midfield. Shilton was tested for the first time as Olaf Thon launched a stinging right-footed effort, and two minutes later he was forced to tip Klaus Augenthaler’s firm drive over the bar. As the half-time whistle blew Germany were on top, but it would have been hard for anyone to dispute the fact that England had been the better side over the entire course of the forty-five minutes.

The second half started off far better for Franz Beckenbauer’s side than the first had done; both Matthäus and Thomas Häßler were starting to find space as the midfield appeared to open up, but it was Olaf Thon who was looking increasingly sprightly. With just over fifty minutes gone, the little number twenty forced Shilton into another fine save. Some ten minutes later, the Turin crowd finally got their first glimpse of the swashbucking Matthäus. Having dispossessed the languid Chris Waddle the German skipper charged down the left touchline, leaving Waddle in his wake and skipping a desperate sliding challenge from Des Walker. There would be no final flourish as he unluckily lost his footing as he prepared to cross the ball into the box, but it was a clear indication the men in green had slipped into another gear.

Germany kept up the pressure: less than two minutes after Matthäus had made his run down the left, Häßler jinked down the centre of the field and was clipped by Mark Wright just outside the penalty area to Shilton’s left. The Germans had won a free-kick in similar fashion in the semi-final four years earlier in Mexico against France: back then, Andreas Brehme’s shot had squirmed under the body of French keeper Joel Bats to give Germany a 1-0 lead. It would be that man Brehme once again in Turin, and although on this occasion the ‘keeper was not to blame the result was equally freaky. The blond full-back’s shot looked to be going wide but it instead took a wicked deflection of the fast-advancing Paul Parker, causing the ball to loop high in the air. As Shilton desperately scrambled backwards towards his own goal-line, the ball dropped behind him and into the back of the net. The deadlock had been broken.

Once more the momentum shifted as England started to force themselves back into the game. Within minutes of Germany taking the lead, Stuart Pearce was perhaps unlucky not to level the scores as he headed wide with Illgner beaten: once again, it had been the impressive Gascoigne who had been the provider. Moments later Gascoigne appeared to have put Waddle through, but the ever-reliable Jürgen Kohler somehow made up the ground to swipe the ball away from the feet of the England midfielder as he bore down on the German goal.

Having replaced the darting Häßler with the more defensively-minded Stefan Reuter, it looked as though Franz Beckenbauer had settled on holding their lead; England meanwhile had replaced defensive stalwart Terry Butcher with a more versatile Trevor Steven. As the match headed towards the end the ninety, England threw everything forward in search of that elusive equaliser – and with ten minutes left on the clock, it finally came. Bobby Robson’s side had been piecing together a number of moves through the midfield – orchestrated in the main by Gascoigne. However the goal came not from one Paul but another in Paul Parker, who lofted what could best be described as a hopeful ball from the right touchline into the German penalty area. Any one of three German defenders could have easily dealt with the situation, but instead made a complete hash of the clearance which allowed Gary Lineker to score his thirty-fifth and possibly most crucial goal for England.

As the ball landed in the area, it bounced and bobbled past both Augenthaler and Kohler who seemed to be performing a rather bizarre duet – while Thomas Berthold appeared to be doing a dance of his own as he desperately backheeled at thin air. It fell perfectly for the ever-alert Lineker, who seemed to be only person in the box who knew what he was doing. Kohler’s slide was too late, as Lineker beat Illgner with a sharp turn and clinical left-footed finish that would have been worthy of the great Gerd Müller himself. 1-1.

As the final minutes were played out and the whistle approached, it had seemed almost inevitable that the match would end in stalemate. The two sides had met three times in previous World Cup finals, and on every occasion the game had ended level after ninety minutes. In 1966 and 1970 the score had been 2-2 at the end of the ninety minutes with both sides taking turns to win in extra-time, while their second-round group encounter in Spain in 1982 had resulted in a 0-0 bore-draw. As in 1966 and 1970 the game would go into extra-time, but this time with with the likelihood of a tie-breaking penalty shootout should the game remain deadlocked.

Both teams started the extra half hour positively, with the energetic Gascoigne looking particularly dangerous. However the most clear-cut opportunity went Germany’s way with just under five minutes gone: after Olaf Thon had found Andy Brehme in space on the left, the full-back’s pinpoint left-footed cross found the head of the hitherto anonymous Jürgen Klinsmann who rose above Des Walker to power a firm header downwards towards the England goal. A foot in either direction would have given the Mannschaft the lead, but Shilton pulled off a stunning save to keep the score at one apiece. No more than a minute later Klinsmann should have put his side in front: after Klaus Augenthaler had delivered a neat clip into the box, the Internazionale striker hit a first-time shot with his left foot, screwing the ball wide with Shilton flat-footed. Germany were now on top, and it was a serious let-off for an England side that were coming under increasing pressure.

In what had been an exciting passage of play that had seen these two excellent German chances, the pressure built up even further when Gascoigne’s desperate lunge for the ball caught the heels of Thomas Berthold who went tumbling. While there was contact made and the challenge was certainly late, it clearly didn’t elicit the elaborate roll from Berthold – or the yellow card that was flashed in Gascoigne’s direction by the Brazilian official that would rule England’s new young hero from a possible World Cup final appearance. The play was now swinging from one end to the other, and there was almost a twist right at the end of the first period of extra time as Waddle found himself in space to hit a firm left-footed shot that crashed against the inside of the far post with Illgner rooted to the spot. This first fifteen minutes had produced far more chances for both sides than the previous ninety, and yet the score somehow still remained locked at 1-1 when it could have been 2-1 to either side, 2-2 or even 3-2 to Germany.

The second fifteen minutes started as frenetically as the first had ended, with both sides looking to finish it before the dreaded Elfmeterschießen. Karl-Heinz Riedle was causing havoc in the England box at one end while Gascoigne’s skill lured Andreas Brehme in to a rash challenge at the other, earning yellow card for the German number three. From the resulting free-kick the men in white did get the ball in the net, but David Platt was clearly offside.

As the play switched sides yet again, a curling effort from Thon forced Shilton into a neat flying catch, Brehme thundered a right-footed effort just over the bar and a charging run down the right flank by the rejuvenated Klinsmann was expertly dealt with by the efficient Des Walker. With three minutes to go, it was Germany’s turn to hit the woodwork as Guido Buchwald’s nicely-timed effort from just outside the area pinged off the right post. The game had finished 1-1 when either side could have scored a further two or three; it was quite clear that the fates had wanted to see a penalty shoot-out.

When Brazilian referee Jose Ramiz Wright blew his whistle to bring an end to what had been a dramatic thirty minutes, both sides were left to readjust themselves; after what had more than two hours of football, the match – and a place in the World Cup Final – would be settled on what could best be described as a ten-minute spot-kick lottery.

Historically, Germany had something of a head-start in their experience of the dreaded Elfmeterschießen: they had failed in their first attempt in the European Championship final against Czechoslovakia in 1976, but had more than made up for that with victories over France in the semi-final of the 1982 World Cup and hosts Mexico four years later. England meanwhile were having to face up to their first such experience.

It was England who would take their first penalty, and their star man Gary Lineker stepped up. Lineker had calmly dispatched two spot-kicks in his side’s dramatic quarter-final victory over Cameroon, and calmly slotted the ball to Illgner’s right as the ‘keeper dived the wrong way. 1-0 to England.

Five years earlier in Mexico City Andreas Brehme had faced Peter Shilton from the penalty spot, only to have his kick turned around the post by the England stopper who had dived superbly to his left. The Germany number three decided to go for the other corner: once more Shilton had judged the direction of his dive correctly, but on this occasion Brehme had delivered a far more precise shot. The ball skidded into the net. 1-1.

Peter Beardsley now stepped up for England, and crashed his penalty into the back of the net with aplomb. Illgner this time went the right way, but he was just too late as Beardsley’s right-footed shot rocketed past him to put the Three Lions back in front. Germany skipper Lothar Matthäus was next up, and he smashed home his kick with even greater nonchalance. It was blasted to Shilton’s right, and although once more the ‘keeper judged his dive correctly the kick was just too good. 2-2.

Aston Villa’s young midfielder David Platt – the hero of England’s last-second extra-time second phase win against Belgium – was next up. He hit his shot firmly to Illgner’s right, and the ball was just once again a little too fast for Illgner. The 1. FC Köln man had read the kick correctly and flown to his right with both hands outstretched, but was a fraction too late as the ball bulged the back of the net. 3-2 to England.

Both goalkeepers had been reading the kicks perfectly – Shilton in particular – but up to this point the penalty-takers were just that little bit better. Shilton once more guessed correctly when substitute Karl-Heinz Riedle took Germany’s third penalty, but once more the shot was just too firm and just too accurate as it flew high to the ‘keeper’s left. Six penalties taken, all six converted – 3-3.

Stuart Pearce had been a regular penalty-taker for his club side Nottingham Forest; blessed with a hard shot, he had proved himself as one of the best penalty-takers in the English league. His left-footed shot was firm and on target, but blasted straight at Illgner’s legs. The ball ricocheted out, Illgner raised his fist in the air, and Germany had grasped the advantage. It was now theirs to lose.

The Mannschaft’s fourth penalty was taken by little Olaf Thon, who scored what was probably the best penalty of the evening. Coming in off a short run, he calmly side-footed the ball into the back of the net. For the fourth time in four attempts Shilton read the kick correctly, but could do nothing as it flew past him to his left. Thon broke into a beaming smile and pumped both fists: it was now 4-3 to Germany, and they were almost there.

It was now up to playmaker Chris Waddle to keep England in the tie; if he scored the pressure would be on Germany’s fifth kicker – in all likelihood Thomas Häßler or Jürgen Klinsmann – to seal the shootout. If he missed, it was all over. Charging in off a run starting outside the D, Waddle struck the ball powerfully with his left foot. Illgner once more dived the right way, but was nowhere near to getting a touch on it. Not that he needed to – as Waddle appeared to lean back at the point of contact, the ball ballooned up over the crossbar and high into the Italian night sky. The drama was over. There would be no fifth kick for Germany: they were through.

Franz Beckenbauer’s side would meet Argentina in a repeat of the 1986 final four days later; it would be a match that could best be described as forgettable, ruined by an Argentinian side that had throughout the tournament ground down the opposition with a mix of negative and dirty play. Not unfamiliar to taking advantage of such situations, the German side were not wholly innocent either – but there was no doubting that they had been the best side of the tournament. England meanwhile had earned the right to one more game, a well-contested third-place playoff which saw them lose by the odd goal in three to the hosts Italy.

For their performance and conduct throughout the tournament, England were awarded the fair play award; Germany, meanwhile, had walked off with their third and and record-equalling world title. It more or less summed up the nature of the long-running duel between the two countries: England had been deemed the fairest, but Germany were the best.

Unlike the dignified players on the field in Turin, even in defeat the English press couldn’t lock their silliness away after the final whistle had blown. While the low-rent tabloid The Daily Star screamed Kr-Out!, the only slightly more upmarket The Sun was only marginally more eloquent with Kraut We Go – accompanied by the obligatory image of the blubbing Paul Gascoigne.

The next meeting between the two sides would take place the following year at Wembley. By that time, Germany would be reunified and fielding a team that included a number of players from the former GDR; both sides would also be playing under new coaches.

Cumulative Record

Home: played 11, won 3, drawn 3, lost 5. Goals for 16, goals against 25.

Away: played 8, won 2, drawn 0, lost 6. Goals for 8, goals against 24.

Neutral: played 4, won 2, drawn 1, lost 1. Goals for 4, goals against 6.

Overall: played 23, won 7, drawn 4, lost 12. Goals for 28, goals against 55.

Competitive: played 6, won 3, drawn 2, lost 1. Goals for 9, goals against 8.